From an unexpected encounter at the bar at the Hyatt Hotel in Tokyo, Japan, a brief but intimate friendship arises between two strangers. Bob, a fading middle-aged American movie star finds himself in Tokyo for a lucrative Whiskey commercial, and Charlotte, a conflicted newlywed and recent Yale Philosophy graduate accompanies her photographer-husband on a business trip to Tokyo. Based on a simple story, Sofia Coppola’s film ‘Lost in Translation’ delves deeply into the inner lives of two indivuduals who’s souls connect for a brief moment. As unrealistic as the chance meeting might be, it is as heartfelt. It is not an affair of the flesh, but one of the mind and spirit.

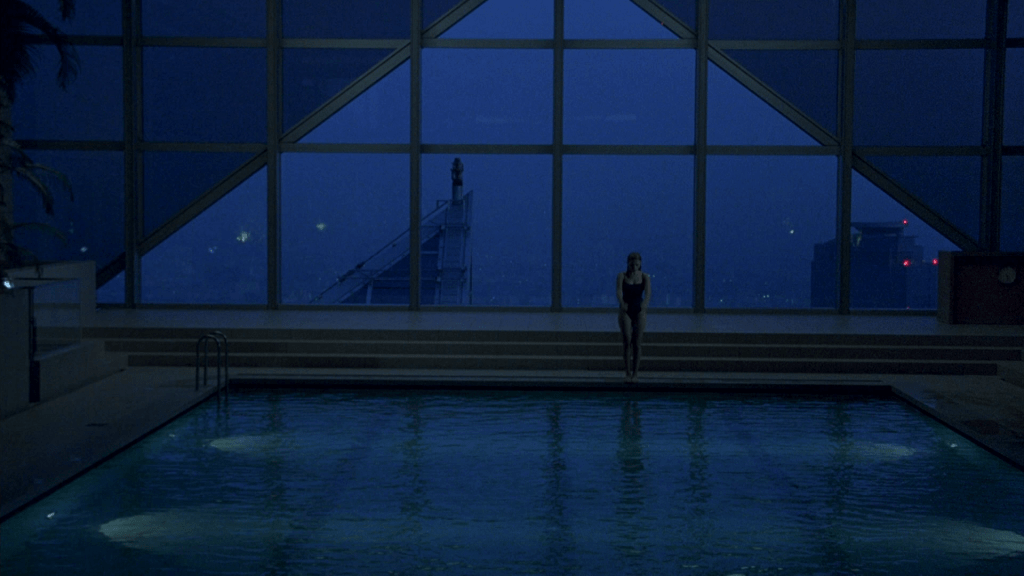

Drifting in and out of scenes of the hotel swimming pools, corridors and bar – the destination of the sleepless and wounded souls – Sofia Coppola explores identity in ‘Lost in Translation’. Both Charlotte and Bob grapple with directionlessness and loneliness in their lives – Charlotte is discontent with the direction her life and marriage is taking, and Bob with the marriage and life he has lived; separated by decades in life, but united by crisis – one in quarterlife, and one in midlife.

Exploring the search for human connection and meaning in moments in life – sometimes young, sometimes old, sometimes following an impactful life event – ‘Lost in Translation’ is at its core a film gifting us a brief glimpse into a difficult time in two person’s lives. As a slow-paced, quiet and introspective film, with a script where silence is as expressive as words, the film thrives on the nuances of those beaten by life’s banality. And still, it captures the beauty in the mundane of the small moments of everyday life with poetic grace, lending the film an ethereal and dreamlike quality. The soft glow of a Tokyo sunset; the hushed quietness of a late-night encounter. Each frame is subdued in quiet placid wonder. Set against the citylights of Tokyo as backdrop, and accompanied by a mesmerisingly atmospheric Japan-pop soundtrack, it leaves its viewers longing to be lost in Tokyo along with the lead roles.

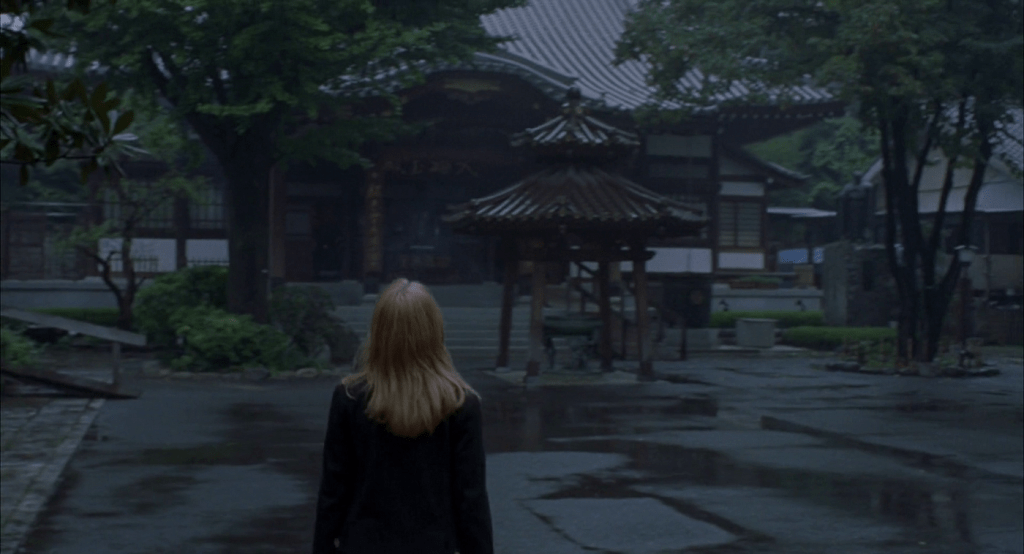

As Charlotte and Bob meditate on loneliness and unfamiliarity at the turn of the century, an era beridden with financial turmoil and uncertainty, the film resonates intimately with its millennial audience. Grossing almost $120 million on a $4 million budget, the Oscar-winning independent film of Sofia Coppola is undoubtedly a cinematographic success. Although well received, Lost in Translation is undeniably critiqued for its unnuaced presentation of Japanese and Eastern culture. However, as the film strives not to depict the East as it is, but to depict two Americans mostly trapped in an upscale hotel with minimal interaction with the surrounding Eastern metropolitan, its interpretation is uncanningly accurate.

Strangers in a strange land and finding solace in solitude, friendship springs from spending sporadic time together. The union of Bob and Charlotte is beautifully described by Wang as, “Like many of the best relationships, Charlotte and Bob instantly find home in each other: a place where you can ask questions and, even if you don’t receive an answer, feel heard…Translation is often like this: feather light, and serious as a paper cut”. As Charlotte whispers at the end of the film “Let’s never come here again, because it would never be as much fun”, Bob and Charlotte are aware they will probably never meet again. Their connection was intimate, but brief, and only meant to happen at that place and time. It was good while it lasted, and will forever be recollected in memory.

It is a film that recollects memories, both painful and poignant ones, but also reminiscent of those events lost to time but was once impactful and formative to our present selves. It is a film not quick to leave the mind, lingering long after the last credits roll. As Charlotte and Bob part for the last time in the closing scenes, Bob whispers something inaudible in Charlotte’s ear as we part from the film and from Tokyo as the frame zones out, forever lost in translation and remaining an enigma until this day.

Leave a comment